Gathered to Mark Anniversary of Historic Prison Hunger Strike, Advocates Vow to End Solitary Confinement in California

solitarywatch.org

Yen-Tung Lin and Luke Baltay

On July 8 and 9, about a hundred solitary survivors, their families, activists, and scholars gathered in southern California to mark the tenth anniversary of one of the most important events in the history of prison activism: the 2013 hunger strike organized by men held in the supermax Pelican Bay State Prison, which quickly spread throughout California to become the largest prison hunger strike ever held in the United States.

Most leaders of the hunger strike could not attend the symposium held at California State University, Fullerton, because they remain incarcerated. But a group of strike participants released in the last ten years, along with many individuals who helped to organize or support the strike from the outside, mustered to revisit its significance, assess the progress of the movement against solitary confinement, strategize for passage of a sweeping anti-solitary bill in California, and heal with longtime comrades.

While the conference hall brimmed with smiles and hugs, attendees also remained conscious of the thousands still held in isolation, in a state that, despite its liberal posture, maintains one of the nation’s largest populations in solitary confinement.

The road to the 2013 hunger strike began nearly 15 years earlier, in 1989, with the opening of Pelican Bay State Prison in Crescent City, on a remote stretch of forested coastline twenty miles south of the Oregon border. Inside the walls of the facility are 1,056 concrete cells, each about the size of a parking space, designed to reduce contact with other humans to a bare minimum. The units are called Security Housing Units (SHUs), allegedly indispensable to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) for controlling individuals deemed the “worst of the worst.”

In reality, the majority of the men held in Pelican Bay were not there for acts of violence. Instead, they were condemned to indefinite solitary confinement without court-involvement, outside oversight, or sometimes even solid evidence, based on their alleged involvement in prison gangs. This gang status could be “validated” by possession of indigenous cultural artwork, newspaper clippings, or books, or by verbal accusations originating from others in the SHU, who “debriefed” in exchange for their return to the general prison population.

In 2011, 46 percent of the Pelican Bay SHU had been in solitary for over ten years, confined to their cells for 23 hours a day without substantive educational or recreational opportunities, telephone privileges, contact visits with loved ones, or even wall calendars to track the passage of time.

Terry Kupers is a clinical psychiatrist who has interviewed more than a thousand incarcerated individuals and offered expert testimony in dozens of cases across the country. Kupers told Solitary Watch that solitary confinement as practiced in Pelican Bay is designed to achieve conformity by depriving incarcerated people of agency—which is exactly the opposite of what they need. “If we really wanted to rehabilitate people,” he said, “what we would do is to foster agency, so that when they get out of prison, they can create their own life in a healthy way.”

The testimonies of solitary survivors during the symposium showed that this deprivation of agency was often accompanied by gross violations of human dignity, and created room for abuse and brutality by staff. Being locked in solitary puts the satisfaction of even basic needs at the mercy of correctional officers, not all of whom observe even minimal standards of decency. Survivors spoke about being deprived of supplies like toilet paper or personal hygiene items, left freezing or broiling in outdoor pens without water, or subjected to wanton cell searches where their personal items are destroyed.

“Solitary confinement breaks people. People aren’t the same after that,” said Kevin McCarthy, solitary survivor who is now an activist and law student. “If anything, it promotes more violence. It causes PTSD and substance abuse issues, mental health issues. It doesn’t accomplish what they claim it does.”

The humiliation and degradation can be even worse for incarcerated women, whose needs for a measure of privacy and for menstrual products are often exploited as a weapon against them. Niki Martinez, a solitary survivor who spent years in Central California Women’s Facility, spoke of the “dehumanizing, and then the degrading things that they would say—as if we didn’t deserve, or if we had no rights, basically.”

In 1990, represented by the California-based Prison Law Office, residents of the SHU filed a federal class-action lawsuit against the California prison system. In Madrid v. Gomez,the court declared conditions in Pelican Bay SHU unconstitutional for individuals with mental illness, but did not outlaw indefinite SHU placement, and the rampant use of solitary continued throughout the following two decades.

In July 2011, inspired by Bobby Sands, the famous Irish Republican Army member who died after a 66-day prison fast in 1981, dozens of men confined in the unit known as the “Short Corridor” at Pelican Bay SHU organized a hunger strike to protest the use of indefinite solitary confinement and arbitrary gang validation. Nearly all of those in the SHU—and thousands in other state prisons—participated in the July 2011 strike, and another held that fall. But the CDCR failed to meet even the most modest of the hunger strikers’ demands.

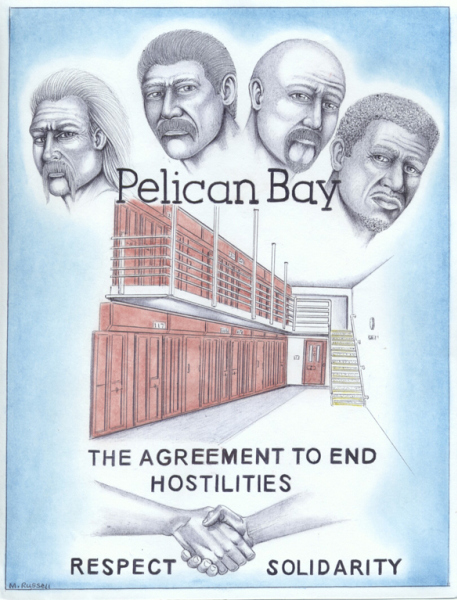

As symposium attendants recounted, in the year following those first hunger strikes, the men on the Pelican Bay Short Corridor drafted and signed the Agreement to End Hostilities between racial groups in California prisons. Racial and ethnic conflict had long pervaded California prisons, sometimes providing a pretext for CDCR’s claim that isolation was necessary to maintain prison safety, and are exploited by rogue correctional officers who would purposefully provoke violence among members of different racial groups.

The Agreement to End Hostilities sought to forestall such actions by uniting the powerless behind the walls, and it exerted a huge influence. “I remember hearing about it, and I wrote a letter home, and I said there is a historical event taking place here at Pelican Bay right now, “ said Jack Morris, who spent more than three decades in solitary. “The end hostility pact changed the atmosphere of the institution, and then it started to spread out to other prisons. And now we’re gonna try to spread it out into the communities. That’s very inspiring.”

Before the start of the 2013 strike, leaders reiterated their core demands: reform of the gang-validation process, an end to indefinite solitary confinement, nutritious food, and substantive educational opportunities. At that time, nearly 4,000 people were held in California’s SHUs; among them, about 500 had been isolated for more than ten years, 200 for more than 15 years, and 78 for over two decades.

The third strike began on July 8, 2013, and soon spread to about 30,000 participants across 33 prisons. It ended sixty days later, on September 5, when the final hundred strikers accepted meals after achieving an agreement with Sacramento legislators to hold hearings on solitary.

The greatest achievement of the strikes, however, was not the victories won through negotiations with the hostile CDCR, but the national and international attention drawn to the suffering of people in solitary. The constitutionality and legitimacy of indefinite or long-term solitary confinement were questioned in the media, courtrooms, and legislative chambers in California and beyond. Jessical Sandoval, director of Unlock the Box Campaign, a national campaign to end solitary confinement, told Solitary Watch that she considers the 2013 hunger strike “the backbone of the anti-solitary movement.”

Kupers pointed out another achievement of the strike: It was a testament to human agency, he said, the exercise of which was itself rehabilitative and empowering: “We’re human beings, we have a voice, we’re going to speak out, and we’re going to attempt to make changes.”

The California hunger strikes were also a model of organizing across prison walls. In 2011, Dolores Canales joined with others with loved ones in solitary founded California Families Against Solitary Confinement (CFASC) to orchestrate outside support by coordinating rallies, press conferences, and community meetings, “because a lot of people were not aware that this was even happening.” A solitary survivor herself, Canales noted that the CDCR publicly attacked the strike organizers, as if questioning their backgrounds or motives could somehow justify the torture of solitary confinement. “They attempted to dehumanize and and criminalize their efforts, and then them as human beings.”

The strikes’ were further amplified by the renowned class action lawsuit, Ashker v. Brown, challenging the constitutionality of indefinite SHU placement and the gang validation process in California. The suit was filed in 2012 on behalf of the 513 long-term residents of Pelican Bay’s SHU by the Center for Constitutional Rights. In 2015, the parties reached a landmark settlement ending indeterminate solitary confinement in California prisons and instituting due process protections for placement in the SHU.

Without the hunger strikes, it was doubtful that the litigation could have made such strides in reforming the California prison system; but without the litigation, the hunger strikes likely would have struggled to solidify their achievements.

In his opening remarks at the symposium, Jules Lobel, University of Pittsburgh law professor and the lead attorney in Ashker v. Brown, highlighted the unique achievements of the case. At its core was a radical model of litigation in which the plaintiffs are front and center, formulating the agenda and strategies, rather than used by their politically savvy lawyers as the pawns for legal reforms. It was the named plaintiffs who outlined the ultimate terms of settlement through countless face-to-face meetings and phone conferences, Lobel said. “We involved the prisoners, and they involved themselves at every step of the way.” In light of the intense isolation and potential retaliation of the CDCR, the depth of the plaintiffs’ participation was even more remarkable.

In spite of these achievements, participants in the symposium also recognized the limitations of their success. The settlement agreement in Ashker has repeatedly been violated by the CDCR, leading to years of monitoring by federal courts. A recent report found that more than 4,700 people remain in solitary confinement in California’s prisons, not counting in its county jails, immigration detention facilities, and psychiatric hospitals, where information is scarce and oversight is grossly lacking. As most panelists at the symposium expressed, what the hunger strikes and the litigation has achieved is critical, but insufficient.

Envisioning the way forward, one session of the symposium was dedicated to the ongoing campaign to pass meaningful anti-solitary legislation in California. The California Mandela Act (AB 280), inspired by the United Nations’ Mandela Rules for the treatment of prisoners and New York’s HALT Solitary Confinement Law, aims to ban the use of solitary confinement on individuals with mental, physical, and developmental disabilities, pregnant people, and people under 26 or over 59; and to limit it for others to no more than 15 consecutive days or 45 days total in any 180-day period.

Jessica Sandavol believes the passage of the California bill would be a “game changer” nationally, especially as similar bills are introduced across the country. Hamid Yazdan Panah, advocacy director for Immigrant Defense Advocates, agrees: “If California were to pass a bill like this, it would send a really important message that the United States as a whole is ready to shift its policy on the use of solitary confinement,” he told Solitary Watch, noting that it would also be the first law in the nation to regulate the use of solitary confinement in private immigration detention facilities.

The Mandela Act was introduced in 2022 and passed both the California State Assembly and Senate, only to be vetoed by Governor Newsom at the last moment. Panah, however, feels that the support from the legislature is even stronger this year. “There’s a lot of new members who are new to the legislature, and a lot of them have been open to supporting this bill,” he said. The bill passed the California State Assembly in May with a veto-proof majority. The Senate vote is scheduled for September.

Even if the Mandela Act passes, California’s movement against solitary confinement will not end. Implementing and monitoring such legislation in the closed environment of a prison can be particularly challenging—something advocates in New York have learned since the passage of the HALT Solitary Confinement Act, as they face pushback from the corrections department and staff unions.

But the mood at the symposium was both optimistic and determined. Just as they have had to fight for basic human rights and dignity, and fight to enforce the Ashker settlement, survivors and other advocates say they will press on with monitoring, litigating, and demonstrating for any legislative reforms they secure. Jules Lobel ended his opening speech by saying: “As we go along in life, we have to cherish our victories, fight against our losses, and always be determined to fight another day. And that’s where we’re at.”

Questions and comments may be sent to info@freedomarchives.org